|

|

Please Whitelist This Site?

I know everyone hates ads. But please understand that I am providing premium content for free that takes hundreds of hours of time to research and write. I don't want to go to a pay-only model like some sites, but when more and more people block ads, I end up working for free. And I have a family to support, just like you. :)

If you like The TCP/IP Guide, please consider the download version. It's priced very economically and you can read all of it in a convenient format without ads.

If you want to use this site for free, I'd be grateful if you could add the site to the whitelist for Adblock. To do so, just open the Adblock menu and select "Disable on tcpipguide.com". Or go to the Tools menu and select "Adblock Plus Preferences...". Then click "Add Filter..." at the bottom, and add this string: "@@||tcpipguide.com^$document". Then just click OK.

Thanks for your understanding!

Sincerely, Charles Kozierok

Author and Publisher, The TCP/IP Guide

|

|

|

Custom Search

|

|

The TCP/IP Guide 9 Networking Fundamentals 9 Fundamental Network Characteristics |

|

Message Formatting: Headers, Payloads and Footers

Messages are the structures used to send information over networks. They vary greatly from one protocol or technology to the next in how they are used, and as I described in the previous topic, they are also called by many different names. Shakespeare had the right idea about names, however. The most important way that messages differ is not in what they are called but in terms of their content.

Every protocol uses a special formatting method that determines the structure of the messages it employs. Obviously, a message that is intended to connect a Web server and a Web browser is going to be quite different from one that connects two Ethernet cards at a low level. This is why I separately describe the formats of dozens of different protocol messages in various parts of this Guide.

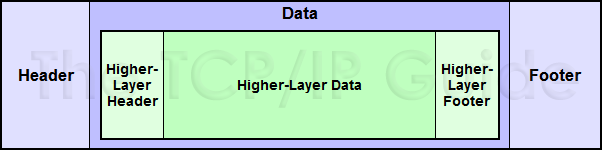

While the format of a particular message type depends entirely on the nature of the technology that uses it, messages on the whole tend to follow a fairly uniform overall structure. In generic terms, each message contains the following three basic elements (see Figure 3):

- Header: Information that is placed before

the actual data. The header normally contains a small number of bytes

of control information, which is used to communicate important facts

about the data that the message contains and how it is to be interpreted

and used. It serves as the communication and control link between protocol

elements on different devices.

- Data: The actual data to be transmitted,

often called the payload of the message (metaphorically borrowing

a term from the space industry!) Most messages contain some data of

one form or another, but some actually contain none: they are used only

for control and communication purposes. For example, these may be used

to set up or terminate a logical connection before data is sent.

- Footer: Information that is placed after

the data. There is no real difference between the header and the footer,

as both generally contain control fields. The term trailer is

also sometimes used.

Figure 3: Network Message Formatting

In the most general of terms, a message consists of a data payload to be communicated, bracketed by a set of header and footer fields. The data of any particular message sent in a networking protocol will itself contain an encapsulated higher-layer message containing a header, data, and footer. This “nesting” can occur many times as data is passed down a protocol stack. The header is found in most protocol messages; the footer only in some.

Since the header and footer can both contain control and information fields, you might rightly wonder what the point is of having a separate footer anyway. One reason is that some types of control information are calculated using the values of the data itself. In some cases, it is more efficient to perform this computation as the data payload is being sent, and then transmit the result after the payload in a footer. A good example of a field often found in a footer is redundancy data, such as a CRC code, that can be used for error detection by the receiving device. Footers are most often associated with lower-layer protocols, especially at the data link layer of the OSI Reference Model.

|

Generally speaking, any particular protocol is only concerned with its own header (and footer, if present). It doesn't care much about what is in the data portion of the message, just as a delivery person only worries about driving the truck and not so much on what it contains. At the beginning of that data will normally be the headers of other protocols that were used higher up in the protocol stack; this too is shown in Figure 3. In the OSI Reference Model, a message handled by a particular protocol is said to be its protocol data unit or PDU; the data it carries in its payload is its service data unit or SDU. The SDU of a lower-layer protocol is usually a PDU of a higher-layer protocol. The discussion of data encapsulation contains a full explanation of this important concept.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

Home - Table Of Contents - Contact Us

The TCP/IP Guide (http://www.TCPIPGuide.com)

Version 3.0 - Version Date: September 20, 2005

© Copyright 2001-2005 Charles M. Kozierok. All Rights Reserved.

Not responsible for any loss resulting from the use of this site.

Key Concept: The general format of a networking message consists of a header, followed by the data or payload of the message, followed optionally by a footer. Header and footer information is functionally the same except for position in the message; footer fields are only sometimes used, especially in cases where the data in the field is calculated based on the values of the data being transmitted.

Key Concept: The general format of a networking message consists of a header, followed by the data or payload of the message, followed optionally by a footer. Header and footer information is functionally the same except for position in the message; footer fields are only sometimes used, especially in cases where the data in the field is calculated based on the values of the data being transmitted.